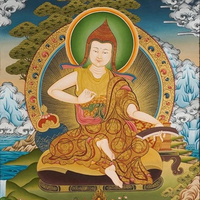

Chandrakirti

Chandrakirti (Zla-ba grags-pa, Skt. Candrakīrti), a pivotal Madhyamaka master, was born, according to most sources, in the 7th century CE into a brahmin family in South India. His early encounters with Buddhist teachings, likely with the teacher Kamalabuddhi, led him to eschew a traditional upbringing and to embrace monastic life. Tibetan texts say that his intellectual prowess led him to Nalanda, the renowned ancient university, where he immersed himself in the study of the Buddha's teachings, mastering texts across various Buddhist schools. It is also noted that he engaged in debates with Buddhist and non-Buddhist challengers such as Chandragomin (bTSun-pa zla-ba, Skt. Candragomin) and that he eventually became the abbot of Nalanda. Tibetan sources describe him as a remarkable meditator who acquired many siddhis, for instance the ability put his hand through stone pillars and even the power to milk a picture of a cow.

Following in the tradition of Buddhapalita, Chandrakirti defended Nagarjuna’s use of prasanga reasoning in his lucid text, Clarified Words: Commentary on (Nagarjuna’s) “Root (Verses on) Madhyamaka” (dBu-ma rtsa-ba’i ‘grel-pa tshig-gsal-ba, Skt. Mūlamadhyamaka-vṛtti- prasannapadā-nāma). The prasanga method refutes opponents’ views by pointing out the absurd conclusions that follow from them. It is in direct contrast with the use of syllogistic logic as promoted by Bhavaviveka in his 6th century commentary on Nagarjuna’s text. In championing the prasanga method, Chandrakirti emphasized that Nagarjuna’s intent was the complete refutation of self-established (inherent) existence and the insistence that conventional truth is established merely in terms of conceptual labelling alone. The various Tibetan traditions understand mere conceptual labelling in different ways. Gelug takes it to mean that what establishes conventional truth is that it is merely what conceptual labels and names refer to; non-Gelug takes it to mean that conventional truth is merely a conceptual fabrication.

Chandrakirti elaborated Nagarjuna’s thought in his Engaging in the Middle Way (dBu-ma-la ’jug-pa, Skt. Madhyamakāvatāra) and his Autocommentary to “Engaging in the Middle Way” (dBu-ma-la ’jug-pa’i bshad-pa, Skt. Madhyamakāvatārabhāṣya). Mostly ignored in India, the only known Sanskrit commentary was written in the 12th century by the Kashmiri scholar Jayānanda, who had traveled to Tibet and had gone on to become the National Preceptor of the Tanguts.

Prior to Jayānanda’s visit, Engaging in the Middle Way had been translated into Tibetan in the 11th century. It only gained prominence in Tibet, however, in the 14th century. In the ensuing centuries, it became the main text for the study of Madhyamaka philosophy in Tibet. The Tibetan commentators ascribe to Chandrakirti and, before him, to Buddhapalita to be the main sources of the Prasangika division of Madhyamaka. The Svatantrika-Prasangika distinction, however, was never drawn in Indian sources.

Chandrakirti also wrote commentaries on other Madhyamaka texts:

- Commentary on (Nagarjuna’s) “Sixty Verses of Reasoning” (Rigs-pa drug-cu-pa’i ‘grel-pa, Skt. Yuktiṣaṣṭīkā-vṛtti).

- Commentary on (Nagarjuna’s) “Seventy Verses on Voidness” (sTong-nyid bdun-bcu-pa’i ‘grel-pa, Skt. Śūnyatāsaptati- vṛtti)

- Commentary on (Aryadeva’s) “Four Hundred Verse Treatise on the Actions of a Bodhisattva’s Yoga” (Byang-chub sems-dpa’i rnal-’byor spyod-pa bzhi-brgya-pa’i bstan-bcos kyi tshig-le’ur byas-pa’i ‘grel-pa, Skt. Bodhisattvayogacārya-catuḥśataka-ṭīkā).

In addition, his Treatment of the Five Aggregates (Phung-po lnga’i rab-tu byed-pa, Skt. Pañcaskandhaprakaraṇa) elaborates the Madhyamaka presentation of the mental factors.

Chandrakirti's contributions to Buddhism endure as a testament to his intellectual depth and spiritual insight. By elucidating the Middle Way, he provided a path that navigates beyond the extremes of existence and non-existence, offering a vision of liberation grounded in wisdom and compassion, affirming his place as one of the luminaries of Buddhist thought.